Fan and Ana and Mary and …

It’s Black History Month here in the United States, a time for all of us to benefit from learning more about the history, role and contributions of African Americans in this country.

A time when “The Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Gallery of Art, National Park Service, Smithsonian Institution and United States Holocaust Memorial Museum join in paying tribute to the generations of African Americans who struggled with adversity to achieve full citizenship in American society.”1

And a good time for those of us who, like The Legal Genealogist, have recorded enslavers in our family trees to contribute what we can to preserving the history of those our ancestors held enslaved.

I continue to wish there was one central consolidated database to enter this sort of information, to ensure it would be retained through the years and decades and — yes — centuries to come. I keep hoping that either the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture or the new and soon-to-be-opened International African American Museum in South Carolina will step up and set this up.

In the meantime, we can contribute to the wide variety of projects that do collect such data — there’s a great list and many resources on the Reparative Genealogy page of the Reparations4Slavery website2 — and keep looking for and documenting the enslaved in our own family histories.

For me, today, it’s a time to say their names.

Fan. She was held enslaved by my third great grandfather William M. Robertson in Columbus, Lowndes County, Mississippi, in the 1830s. Her existence was documented in the deed books when William used her as security for a loan of $155.40 for his hat shop: “a certain negro woman by the name of Fan supposed to be about the age of thirty five years.”3

She was not the only person held enslaved by William. The 1830 census records one enslaved man aged 36-54.4 By 1840, he held 12 people enslaved: a boy under age 10, two males 10-23 and one 24-35, four girls under age 10, three females ages 10-23, and one 24-25.5 He was not recorded as an enslaver on the slave schedules thereafter, but his son was.

My second great grandfather Gustavus Boone Robertson was recorded as an enslaver on that 1850 slave schedule, in Winston County, Mississippi.6 He held two women — one age 30 and one age 50 — enslaved; thus far, no record of their identities can be found.

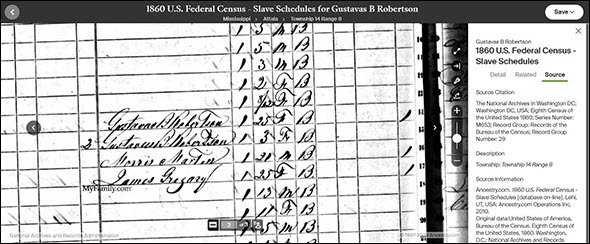

He was recorded again as an enslaver on the 1860 slave schedule, in Attala County, Mississippi. There, he was recorded as enslaving one woman aged 25 and one little girl, aged three7 — and that leads to the other two names that I know.

Ana and Mary. The family story is that the nanny of the Robertson children had chosen to go with the family when they left Mississippi just after the Civil War to settle in Texas. I have my doubts about the voluntariness of any such move, but it’s undeniable that — enumerated in 1870 next door to Gustavus and Isabella and their brood of children (10 by then living at home) — were two people who almost have to be those enslaved females of 1860.

Ana Robertson. Age 36. Black. Born in Mississippi. Mary Robertson. Age 13. Black. Born in Mississippi.8

It looks very much like these folks stayed in Lamar County after my Robertsons moved on to Delta County. There’s an Annie Robertson enumerated as the mother-in-law in the household of Nathan and Mary Shirrell in Lamar County in 1880. Annie, age 45, and Mary, age 23 — both born in Mississippi.9 I haven’t yet located the family after 1880.

Fan. Ana. Mary.

Here, in Black History Month, I say their names.

Cite/link to this post: Judy G. Russell, “Say their names…,” The Legal Genealogist (https://www.legalgenealogist.com/blog : posted 2 Feb 2023).

SOURCES

- Homepage, Black History Month (https://blackhistorymonth.gov/ : accessed 1 Feb 2023). ↩

- “Reparative Genealogy,” Reparations4Slavery.com (https://reparations4slavery.com/ : accessed 1 Feb 2023). ↩

- Lowndes County, Mississippi, Deed Book 1:55, Deed of Trust, Robertson to Tucker; digital images, DGS film 008567186, image 37, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ : accessed 1 Feb 2023). ↩

- 1830 U.S. census, Lowndes County, Mississippi, p. 84 (stamped), William M. Robertson; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Feb 2023); imaged from NARA microfilm M19, roll 71. Note that the Ancestry index entry recording an elderly enslaved woman is incorrect; the indexer appears to have misread a tally mark intended for another purpose. ↩

- 1840 U.S. census, Winston County, Mississippi, p. 266 (stamped), person; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Feb 2023); imaged from NARA microfilm M704, roll 219. ↩

- 1850 U.S. census, Winston County, Mississippi, slave schedule, p. 59 (penned), “Gustavius Robinson”; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Feb 2023); imaged from NARA microfilm M432, roll 390. ↩

- 1860 U.S. census, Attala County, Mississippi, slave schedule, Township 14 Range 8, p. 26 (penned), Gustavus B. Robertson; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Feb 2023); imaged from NARA microfilm M653, roll 595. ↩

- 1870 U.S. census, Lamar County, Texas, population schedule, Beat 2, p. 253B (stamped), dwelling/family 308, Ana and Mary Robertson; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Feb 2023); imaged from NARA microfilm M593, roll 1594. For the Gustavus Robertson household, see ibid., dwelling/family 307. ↩

- 1880 U.S. census, Lamar County, Texas, population schedule, Paris, enumeration district (ED) 81, p. 213C (stamped), dwelling 166, family 202, person; digital image, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed 1 Feb 2023); imaged from NARA microfilm T9, roll 1314. ↩

* This article was originally published here

Colburn Hintze Maletta is a Phoenix Criminal Defense and Family Law Firm. Visit them at https://chmlaw.com

Social Plugin